I find myself again

thinking about the video game Limbo created by studio Playdead. The game

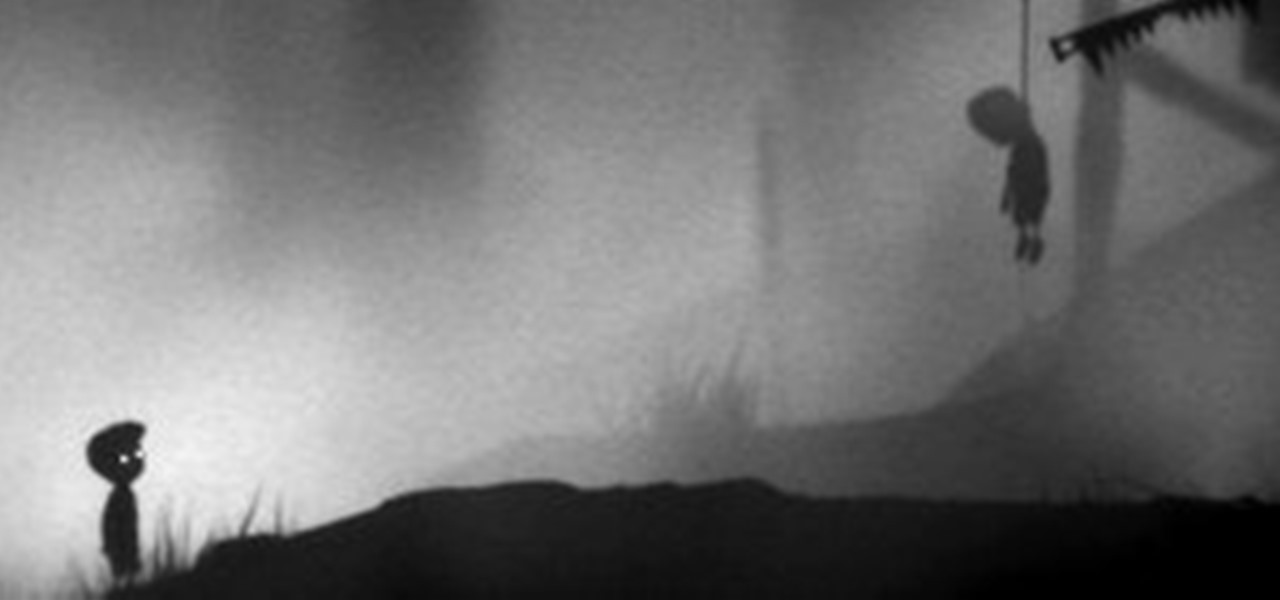

involves your character, a young boy, wakening in a dark wood alone and then

journeying through a dark world in order to find his sister. Along the

way the little boy encounters all sorts of hostile traps, a William

Golding-esque tribe of little boys out to kill him (with a worm-infected Piggy

drowning in front of him), and a giant Ungoliant-like spider dogging his

steps. Eventually he avoids the traps, tribes and spider and comes to the

end of his journey, naked and alone, to meet a female figure (presumably his

sister) playing in the dirt beneath a treehouse.

An excellent analysis of

the game is posted by Jake Vander Ende at Aletheia's Herald in which the author

recognizes the game as a trope of Dante Alighieri's great work "The

Inferno". Vander Ende notes rightly the strong correlation of the

opening of the game with Dante's opening cantos awakening in a dark wood.

Further, the somber and violent nature of the game strengthen the connection

between the two works. Also he notes the river crossings and marshes as

similar in setting to the river crossing of Acheron and the marsh areas of

upper Hell. Vander Ende also seems correct in noting the transition

midway through the game to a violent mechanized cityscape as similar to the

transition into lower Hell through the gates of Dis.

I very much agree with

these connections. The game seems very intentionally troping all these

powerful images from Dante. I don't entirely agree, though with Vander

Ende's comparison of the spider to the beast, Cerberus - despite the

"feeding of earth" to both creatures. Cerberus is a monster of threes

(three heads) while the spider is a monster of eights (eight leg).

Moreover, Cerberus is a dog; a very different iconic image than the arachnid

image in Limbo. Also, Cerberus is the first but not the only giant monster encountered in the work; Geryon and Satan himself come to mind. Finally, though matter is thrown into the maw of

Cerberus, the spider is crushed by the rock. These seem too distinct to

reach a good comparison.

The article at Aletheia's

Herald also compares the butterfly to Virgil. Though they have similar

characteristics (the guiding nature of each, the connection to the female

figures of Beatrice and the sister, and the "living" characteristics

of both the Latin poet and the bug) I don't think they can be made an

identity. Further, Virgil in Dante's poem is in Limbo and is called out

by Beatrice to reach Dante. Nevertheless, Virgil remains a permanent

resident in Limbo and vanishes at some point during the second of the three

Cantiche. This, I think, excludes the butterfly, a non-human figure

symbolizing immortality, from fully embodying the Virgil image. Moreover,

the butterfly is traditionally seen as the image of the soul emerged from its

sleep (in the chrysalis) - transformation from being trapped in darkness to

resurrection into life. Therefore it may be a reminder but isn't

necessarily a guide.

Finally, Vander Ende

writes that during Act III of the game

"You no longer have angry people defending their territory or whatever, but instead you have pure mechanisms of wanton violence designed to obliterate everything animate and inanimate in their path"

Also, the game's traps

become brobdignagian in size suggesting the titanic forces of Dante's giants

near the last rings of hell and the giant figure of Satan himself. Vander

Ende writes

"the 9th circle is ringed by giants, just as the end of the game is marked with huge gears that dwarf the main character and are never completely visible on screen because of their size. The gears are essentially automaton giants guarding the final areas of the game..."

Though I think Vander

Ende is spot on in seeing the parallels between the two works, and undoubtedly

much of Dante is filtered through the designers into the game, I think the key

is in the fact that the images are “filtered”.

This process seems to be how great art is made. Bad art is like a photocopy – it tries to

make a direct parallel between itself and some other great work; like putting a

piece of literature onto the screen and slavishly repeating every line from the

book verbatim. As Tolkien himself noted

this sort of thing is not possible. A

depiction, like a translation, is a form of interpretation. The images inevitably contribute something

new to the meaning, alter the iconography, tell their own story and if the

artist refuses to acknowledge this their art inevitably becomes inferior. If, however, an artist uses the imagery of a

great work to tell their own story they are exercising what Bernard Batto

speaks of in his work “Slaying the Dragon” as mythopoeic speculation. Here the little boy slays his own Dragon of sorts, but he does not do so in an identical way to Dante's method of journeying through words back to the light - in fact the game is conscientiously without dialogue.

Consequently, though the

developers of the game seem to use many elements from Dante and in fact might

base a majority of their story structure and imagery on Inferno, the game seems

to be telling a slightly different story.

So what story is it the

game is telling?

Some clues to consider:

The black and white nature of the game seems to indicate a clash of opposites;

duality; matter and spirit, male and female, like the yin and yang of the tao. The rain and constant water imagery seem to

hint at feminine forces in the unconscious dreamworld of sleep or death. The violent images do seem to increase during

the course of the story moving from childish fears of spiders, heights, and traps

to malicious fellow humans and finally the impersonal violence enacted on us by

in impartial world. There does seem to

be a movement from natural to more mechanical threats as well.

The butterfly has a

connection to the soul and the soul’s flight toward perfection.

The youth of the boy and

his sister seem to indicate the soul as well since the image of the young

maiden/youth, “kore” in Greek, traditionally represents the soul.

The brain worms seem to

suggest a perpetuity of the puerile and zombielike activity of youth – the worm

being the first of three forms of metamorphosis of the butterfly.

Perhaps, then, one solution

to the game is tied into the term “Limbo” itself. Though the game seems to parallel Dante, it

is not a Hell but a perpetual grey day – trapped doing the same thing again and

again and returning to the spot you thought you left. The journey for the boy, then, seems to be to

escape Limbo lest it be Hell. He, like

Dante, goes through an interior journey personal to himself into which the

nuisances, threats, and fears of the exterior world manifest as lethal dreamlike

images. Broken from his beloved self,

the rational, masculine, conscious side (indicated by the glowing eyes) journeys

through this world of images, striving to survive, and reunite with its feminine,

irrational, contemplative, subconscious side.

Orpheus seeks his Eurydice,

Dante seeks his Beatrice. In each image

the rational is insufficient; deprived of its spiritual feminine element,

deprived of love and desire, it falls into a routine, then into a despair, then

into a spiritual death. Days pass into

days and all life seems meaningless.

This is the story of the Fisher King, who is wounded in its sexuality,

suffering the dolorous stroke, and whose lands fall into parched ruin. This is the rain, image of the feminine, that

falls from the divine realm and heals the land of T.S.Eliot’s “Wasteland”. This is the transformation by means of rain

of the red wheelbarrow of William Carlos Williams.

Our hearts long for wholeness,

for home (the treehouse), call it “god” or call it “Beatrice” – for Dante one

simply led to the next, ever opening into greater repeated forms. “You have made us for yourself, O Lord,” wrote

Augustine, “and our heart is restless until it rests in you.” When we no longer see the glory and beauty of

life, when we are no longer in love with the world around us, things become

dull, lifeless, grey and repetitive.

Shakespeare’s character, Hamlet, experiencing this condition bemoans;

How weary, stale, flat, and unprofitable

Seem to me all the uses of this world!

Fie on't! O fie! 'tis an unweeded garden,

That grows to seed; things rank and gross in nature

Possess it merely.

Seem to me all the uses of this world!

Fie on't! O fie! 'tis an unweeded garden,

That grows to seed; things rank and gross in nature

Possess it merely.

At that point of

existence we see nothing but cold rain, violence from other people, the random

machinations of a hostile world. The

world becomes, as John Paul II said, “a bad night in a bad hotel.” Limbo.

And in such a state, should we “die”, the world would become Hell. Even Dante himself recognized this perilous state. Having suffered defeat at the hands of the Black Guelphs, having been banished from his native Florence and having seen

all his political aspirations fallen into the sewer he might have been close to

despair. The Inferno suggests his

condition on the brink of suicide through linguistic parallels between his

opening cantos and the cantos containing the wood of the suicides.

The trick, then, is to

try to get back home; to be born again and see the world as “charged with the grandeur

of God.” Such a return would unite the

subconscious with the conscious. The

game’s ending suggests a tree house still intact. The recognition of the girl to the boy’s

presence doesn’t seem to be startlement as much as breathless anticipation. The last scene is suffused with light. The boy falls through, not a glass window,

but a skein of water – sideways – as though emerging from the birth canal into

the world. Even the comparison of the

boy waking up in the first woods compared to the last seems to suggest an

ending that reunites the two. The first

woods is lonely and hostile. The second

is peaceful and culminates in the feminine love interest. The boy travels uphill to meet the girl,

symbolizing his journey up toward the light.

Seen from this

perspective I am reminded of St Teresa of Avila’s statement that “In light of

heaven, the worst suffering on earth will be seen to be no more serious than

one night in an inconvenient hotel.” The

boy and the girl together seem to escape this Limbo hotel, barely passing out

of the grinding gears of ever lowering death – just as, in the dance, the bar

is lowered - into life.

(The Limbo) dance is also used as a funeral dance and may be related to the African legba or legua dance."Consistent with certain African beliefs, the dance reflects the whole cycle of life....The dancers move under a pole that is gradually lowered from chest level and they emerge on the other side as their heads clear the pole as in the triumph of life over death".

At the last scene, then,

years in the future, the house is in ruins and what seems to be the graves of

the children or child lie beneath it.

But the scene is suffused with light.

And since it is the last scene in this Limbo world of perpetual sorrow,

the significance seems to be that the children haven’t died but have passed,

finally, from death into real life.

I certainly enjoyed reading Vander Ende's article as it sparked again in me an interest in this game. Now I must go replay it; and play the second of their creations - Inside.