A recent exchange with a graduate.

Dear Abecedarius,

Far be it from me to convert to paganism, but the Greeks' insight is starting to make it sound attractive.

Greeks had (as far as I know) two versions of the deityEros:

Eros was not only erotic love and beauty but also the personification of the creative force, one of the primordial gods.

The other version has Eros the god of romantic love, son of Aphrodite and Ares, and being a chaotic, mischievous force.

To some degree, Greek Polytheism seems to be the attempt to reconcile the unity of goodness and its many, often conflicting, manifestations. Zeus is a powerful god who in a sense stands for unity and goodness, but when the question is asked "From where comes evil?" we get comical images of the apathetic Zeus sleeping around. It's almost as if the Greeks knew goodness was one and was powerful, and that there was evil, and having no way to reconcile these two ideas, they made a farce of it by manifesting different goods in different gods so that they could conflict.

This is where the two versions of Eros come in. In the first sense, erotic infatuations are the most providential of human affairs, originating in being qua being himself more directly than any other passion; in the other sense, erotic infatuations are some divine anomaly (as many objectivist biologists like to think today) that are the result of a rebellious, chaotic and mischievous force, thus making erotic infatuations outside of divine providence. Both ideas seem to be common today, and both seem problematic.

On one end, an idol is made of Eros, and the items of worship range from modern innundation of Harlequin novels, to various television shows, to unhealthy obsessions that control lives, particularily high school girls. Eros is trusted as if he were God Himself, and current infatuations are taken to be THE infatuation. When Eros breaks one's trust, one can only experience the most nihilistic heartbreak.

On the other end, Eros is killed in the name of stoicism. There can be no romance, but mere sexual drive. Eros becomes a passion to overcome. In the Platonic sense, Eros is an appetitive passion, and the virtuous man controls and exercises temperance with regards to his romantic appetite. The problem with this scenario is that Eros seemingly cannot be controlled; it is by nature chaotic. One cannot chose whom one falls in love with, but can only choose whether to trust providence and pursue the beloved, or to trust his own wits, betray Eros, and pick a more suitable spouse outside Eros's counsel.

I suppose my entire email boils down to one question: Can one fall in love with the wrong person, and what are the ramifications of this?

Sincerely,

Alfred P. Student

~~~~~~~~~

Al,

You just jumped right in there, dintcha?

First, we have to consider that no idea, including ideas about the divine, ever occurs in a vacuum. We have to look at the historical progression of ideas to get a sense of what we are dealing with in the modern world.

Yes, the ancients did see the force of Eros as positive and negative; but they saw all divine forces as such. Man was a pawn in the plan of the gods, subject to the whimsy that changed on a drachma. So Eros was both the beautiful force of attraction to the good, and it was the destructive force that played gin rummy on human lives. What were they talking about? Most probably they were describing that force that drives us to love this or that thing/person beyond our control. For the ancients, to disobey such a force caused ruin and, since life was short, one took what pleasure one could when one could. Carpe diem, said the Latins. Not everyone did this of course (Hector) but all reckoned that this was a force to have to deal with. Euripides’ “Bacchae” is really dealing with just this force of wild abandon and desire; ecstasy. I really believe that the ancients did see these forces as stemming from a central force or being, but they didn’t talk that way. Probably b/c humans must dissect in order to understand anything, so we break the power down to its constituent parts. Even Zeus himself was not the final force or power; he was merely the ruling Olympian god; law and order imposed on others (all of his sexual escapades are actually impositions of law, not eros gone willy nilly; they are rapes, not consensual powwows). This concept of various divisions of one force goes back to Neolithic (Stonehenge and Egyptians) times. Such gods were very real in that they really were thought to walk the earth but they bespoke of a dark and violent force to the world. Originally depicted as snakes, they later morph into animals and protean elemental forces. I don’t think that such a sense of terrifying snakiness has ever left us. We are still, as humans, quite pagan in our outlook on life. (so you can’t convert, you already are!) But history has added nuance to our paganism.

The first nuance was the change during Homer & later Plato’s time. Homer first starts to speak of the gods in a critical way. Not so much to poke holes in the whole polytheistic thing (I don’t think he was thinking that far ahead) but to show that these forces lent themselves to humor and tragedy. He was a radical in his era, but he also made a living by embodying the zeitgeist of the Ionian age. This same criticism is later picked up by the Athenians who see the gods not as gods external to us but as representations of forces within man. For Plato, the gods were a language for talking about those things we experience as humans. Nevertheless, the golden era philosophers seem to have believed that there really was a force of some sort to which man conformed (both physically and spiritually). This force is difficult to speak of directly so we speak of it through a mirror, or shield, which is polytheism. We anthropomorphize in order to understand. But in anthropomorphism a major change takes place. The snakiness disappears. No longer are the gods forces that control us, but they begin to become forces which we participate in (since they are manlike and not “Kadosh: otherness” as the Jews called them). Suddenly the gods become incarnate in man form and are thought to be understood not as beings that walked about the earth, but as forces which we control. No longer is Eros a destructive, whimsical force giving pleasure here or there, but becomes an expression of that longing which every man feels within him for some unknown beauty; the unknown Areopagite god. This unknown god is so beautiful that a man must control himself in order to see him, and sacrifice all else that he has for this richness. So a shift in teleology occurs; nuance is added to our pagan thought.

The next additional nuance comes from the merging of Jewish and Greek ideas. The Jews, who initially also saw the forces as serpents stemming from one serpent, began to conceive of the force as anthropomorphic; Yahweh was a man with hands, feet, breath, eyes, even a backside (which he shows to Moses). Moreover, he was a manlike being who loved his little creatures, instead of merely using them. This is a significant change. If the forces are within us, then the fact that the force loves us gives a teleology to the forces within us which is radically different than previous. This is why I love the mythology and religion of the Jews. God loved us, not only in a sexual way (as the Greek gods did) but in a deeply moving type of love that was beyond even eros. Eros becomes caught up in a greater love of self and other which is what Yahweh displays to his little shepherd idiots. We begin to get an insight through the Jewish faith into a being who loves on many levels; and thus we get an insight into the fact that our loves (whatever those mysterious movements in the soul are) have a greater telos than mere gain or pleasure. The Jews stressed family life as the greatest institution on earth. Man and woman were made to get married (not just to exchange bodily fluids) and within marriage sexual love was the highest expression of love (witness the book of Tobit wherein the demon seeks to block, not the marriage, but the sexual consummation of marriage). Thus for the Jews, women were honored above all else and the having of children was “arrows within your quiver.” Wealth became measured by how much one loved one’s god, one’s family and, by extension, one’s neighbors.

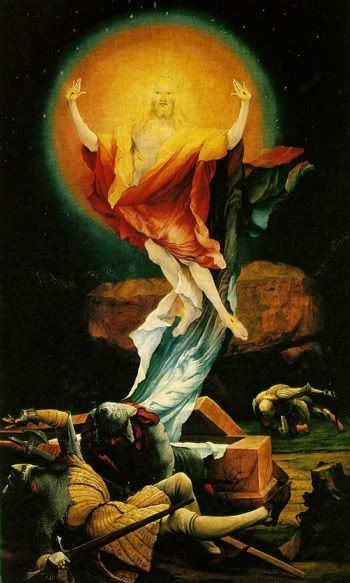

When the Jewish beliefs merged with the golden era Greek philosophy a new concept came into existence which again gave nuance to our paganism. The nuance was a merging of the Jewish concept of love & marriage (esp. as a symbol of God’s love) with the Greek idea of longing and self-control for a greater good. “No greater love hath a man than that he lay down his life for a friend.” In Christ we have the union of the concept of marriage and sex and birth with the concept of self-sacrifice, denial, suffering, resurrection. The Jewish aspect proclaims that “God so loved the world” and that Christ attended the wedding feast at Cana, and that “out of his side flowed blood and water.” The Greek aspect proclaims that “…he gave his only begotten son” and that Christ “suffered and died so that we might have life” and that on the third day he rose from the dead. The belief for men shifts in this nuance from being merely a concept to being an embodied individual; there really was a Christ, he really did bless marriage and friendship, he really did suffer and die and rise again. Thus our belief in the Incarnation changes our concept of ourselves. Not that if he could do it so can we (because that implies that success is merely a force of will) but rather that the focus of the divine force within us is to endure suffering and failure for the sake of the love of others not yet seen. Marriage and sex become a “total gift of self” (to borrow the words of JP2) and even Eros is subordinated to understanding, nobility & honor, and self sacrifice for the good of something greater. That’s one heck of a nuance.

The final nuance, IMO, is that given to the West by the Medievals. The code of chivalry exalts women to the status of quasi-divine creatures. I don’t think this is a new exaltation; I think that men have always had a tendency to do this. But the Medievals gave voice to what this experience is like and in the romances suggested that such a natural exaltation is symbolic of man’s longing for something greater than himself. The knights, ladies, monsters, love affairs, duels, and quests that populate the Medieval romances are themselves a landscape of the human heart wherein man learns how best to focus his own natural desires. Sure we can sympathize with another man on a cross, but my own desire for a woman, esp. one made unattainable by marriage to another, eats at me and conflicts with that image of self-sacrifice embodied by the figure of Christ. How can I be a good Christian when I so desire her? How can my natural drive to procreate with this divine-like being be reconciled with the purity and chastity which Christianity urges me to cultivate? This is the big question of the romances the answer to which gives the final nuance to our paganism. Lancelot’s desire for Guinevere never fades. In fact his perpetual desire for her destroys everything that he has ever believed in; ruins his wife, strips him of all honor, wrecks the court of Camelot, takes the life of Arthur, prevents Lancelot from achieving the Grail, and reduces him to a starving heap of a man. Yet he does not stop loving her. If she is the image of longing which Eros produces that does not bode well for any of us. When does Eros let us go? The answer, I think, is never. But what Lancelot does is remarkable. He chooses to apply himself to an honorable course of life. He chooses to enter the monastery when Guinevere enters the convent. He chooses to do penance for the love that has brought so many to ruin. This choice is the answer to those big questions of desire; we choose honor even if it makes us suffer and die. By doing so, we are not driven about by Eros but have a choice to remain constant to a way of life we know to be right. In so doing we become the greatest of chivalric persons.

Taken altogether, I don’t know if I answered your question. Bluntly, can you fall in love with the wrong person? Sure. Are you driven by love to have to act on that love? Absolutely not. Our “falling in love” comes and goes; Eros still shoots arrows. And in our blackest moments we all of us are pagans. But what the history of thought has shown us is that those black moments do not have to last. Ultimately, our sexual desire and, moreover, the desire of our heart (b/c the two are not entirely separable) will always be for different people. But we are free to choose that person who is right for us (I mean by “right” honorable, financially secure, emotionally stable, supportive of us, and attractive), commit to them, and remain faithful despite the tidal changes of the heart.

Eros is a force, like all the pagan gods, which, if worshipped like a god becomes a demon. He does not command us, we command him. And in the name of honor, self-sacrifice, goodness and happiness, in the name of Jesus Christ, we order him down to his proper place.

Hope this all helps.