You claim the work is mine (the killing of Agamemnon), call me Agamemnon's wife - you are so wrong. Fleshed in the wife of this dead man, the spirit lives within me, our savage ancient spirit of revenge.

(1526-1530)

What a startling admission by the central character that what has been done is the embodiment of our natural human tendency toward violence. We are fallen creatures; and at our heart we are dark and savage. We must, as Robert Fagles points out in the essay "The Serpent and the Eagle" strive for a "...victory... over the barbarian latent in (ourselves), the hubris that unites the invader and the native tyrant as a targets of the gods." This is only possible through "...compassion and lasting self-control" in the pagan world. There is no hope of redemption accept through the wearisome toil of self-control and rational thought which allows us to think through how we are to govern ourselves. Without such thought, without such toil we fall into that cycle of feuding bloodlust that drives even today one clan, one gang, one family to seek the annihilation of the other. Only through law, adherence to self control, and constant exercise of compassion and charity can we hope for a better world.

Klytemnestra, notably enough, is also devoid of any individuality. The revenge murder which she has plotted these 11 years, to which her entire intellect has been turned, has stripped her of individual will and the ability to see reason (or ratio); she is no longer an individual in the LOGOS but an archetype acting as the agent for that "savage ancient spirit of revenge." So do all people who resort to violence over compassion, anger over understanding, dictatorialism over democracy, lose their individual importance and become just another face in the yelling mob of faces. Only goodness is unique; evil is ordinary.

But more, still, for the toil and labor of our own sweat and blood to hold ourselves to the honorable course of self-control and compassion is an impossibility in the long run. You injure mine and I will crush you - "annihilation" as Medea says. In the pagan realm one can marvel at the unique glory achieved through self-control and compassion as a principle, but we fall short, we fail of achieving this glory ourselves and so we end up as victims and losers. Pagan thought offers no solution to this failure. The barbarian latent in ourselves cannot be mastered through our own efforts and so we continue to be pursued by those dark cthonic gods we call "Eumenides".

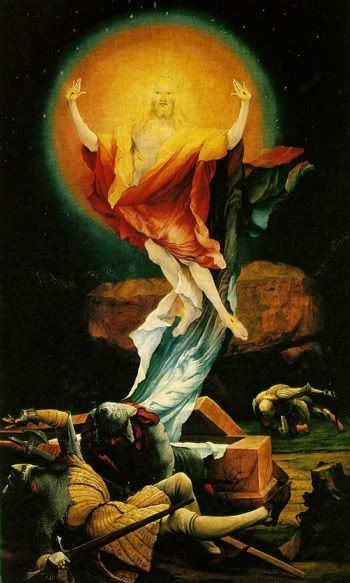

Christianity alone offers any solution to this conundrum for (as Nietzsche pejoratively declared) Christianity is a religion of losers.

Failures.

The weak, the broken, the sorrowful and the crushed.

Christianity is all about not being strong enough to endure the grinding Grendelian churning of the wheel of human nature; we cannot master ourselves, and yet that's okay. In Christ is our hope and our salvation. We die that he might live and all our glory, says St. Paul, is due to him. The failures crucified on either side of the Divine Failure are given hope that their sanctity is ensured, not because of their own broken muscle and sinew, but because they recognize their smallness and weakness and give over their broken and contrite heart to the Lord.

Then

in the midst of that sorrow and failure

a miracle!

for Jesus Christ is born this day

and Lo! he makes all things new.