I was struck this time around teaching Aeschylus of the remarkable nature of this play. Robert Fagles in his illuminative commentary, "Serpent and the Eagle", claims that the Oresteia stands as one of the two greatest works of the golden age (the second being Phidias' Parthenon). Indeed, when one considers the problem of, as Fagles calls it, the perpetual cycle of human barbarity then the Oresteia offers a solution that is unique in history and pivotal to the development of Western thought.

When I teach the work I always begin by reflecting on the idea that drama originated as a bloodless representation of the bloody sacrifice of a goat or man for the sake of the city. The cathartic experience of seeing another living creature die for the sake of the city's sin, literally of witnessing a "scape goat", cannot be underestimated in the modern world. We all still need this cathartic experience which, as Walker Percy points out, seems to elevate us out of our daily life of complacent normalcy. Thus we still go for thrills at amusement parks, sports, movies, games, anything to jolt us out of the dull greyness of life. For those witnessing this early form of ritual violence the result must have been powerful.

But for the victim it was probably no bed of roses. Thus the myth that the goat sang a song of sorrow before being killed; a goat (tragos) song (oidos) that led to the tragedy (tragoidos) of later civilization. Tragedy became the bloodless representation of the bloody ceremony of death that prompts catharsis. The same jolt could be had through seeing simulated violence instead of seeing real violence and thus a civilization gained the merits of the cathartic experience without the barbarity of bloodshed that disrupts with its inevitable consequences. Mythologically, some god must surely have sent this bloodless substitute. Thus Dionysus, it was said, granted to Athens the Dionysiad; the week-long religious festival of dramatic performance. What began as a single chorus chanting the sorrowful dirges of death (perhaps as accompaniment to the impending sacrifice) evolved at some point to a chorus and a single actor (named Thespis for the sake of argument and thus "thespians"); this evolved again into chorus and several speakers and eventually into several individual characters as we have in modern drama.

The tragoidoi were, however, much more like modern religious ritual than modern entertainment. Just as in the modern Mass of the Catholic Church a single speaker (the priest) would lead a chorus (the congregation) in a series of movements, setting, dress, music, and words all designed to create a mythological world separate from daily experience and reinforcing the idea of a greater or elevated reality to human existence. (As a side soap box, the Church used to have, therefore, beautiful music, robes, incense, lighting, a dress code all in existence to create this separate world. Modern Catholicism abandons all this and so losees the whole sense of drama as ritualized transcendence. But that is another issue).

Aeschylus' plays are not too far removed from the chorus and one or two speakers of earlier drama. His play is still a religious iteration of the reality underlying human existence (like someone writing down the words of the Mass read by later generations). Oresteia, Fagles says, is a dramatic retelling of an eternal human story of death and rebirth; a movement from darkness into light. Yet the play also answers the age old question of what to do with human violence.

The problem with our race is that our default state of thought is tribal; we think first and foremeost in terms of The Tribe. Most of our history is a bloody business of violence and retaliation which emerges primarily from thinking in terms of ourselves as members of a tribe rather than of a polis, or city. Tribe does not mean just primitive societies such as Africa or Indians of Brazil or natives of Borneo, nor is tribe merely a question of sanguinity; "our kin". Rather it is a way of thinking about the world that keeps us primitive and violent

I refer, here, to the analysis of David Pryce-Jones in his study of the Middle East, "The Closed Circle". Pryce-Jones sets out three main criteria that distinguish tribal thought from polity thought. Tribal thinking consists of

1. "our group" greater than "their group"; us vs. them; we are blessed and they are damned

2. honor and the gaining of honor as the driving force of society; all is justified in the acquisition of honor

3. coersion as the main force to influence those w/in the tribe; force or violence

All lead to greater violence, retaliation, and more violence. The constant violence in Palestine, Afghanistan and Africa; the gang wars in Los Angeles and Chicago; the bloodshed in Japan all emerge from this form of thinking. How to break this? Can one break this especially since it goes back to the neolithic era or beyond? The cycle of violence seems perpetual; something ingrained in us from the dawn of rational humans. We specialize in slaughtering one another. Nor is our slaughter ended simply by sending Jimmy Carter to the Middle East.

Aeschylus' play suggests, to the contrary, that the perpetual cycle of human barbarity can be overcome.

Yet it can only be conquered by a radical shift in thought. First recognizing that this bloody cycle is a reality, is perpetual, and emerges from thinking in terms of the tribe. Second, Aeschylus suggests that the cycle can be overcome only by triumphing over "the barbarian latent in ourselves"; the hubristic capacity to commit all manner of horrors. This violence is a form of barbarism antithetical to civilization, yet within every person - everyone is capable of committing horrors. Only by triumphing over the barbarian w/in can we possibly break the cycle of violence. But how is this triumph over ourselves accomplished?

Aeschylus suggests, according to Fagles, that it is done by compassion and lasting self-control. The first, compassion, is loving your neighbor as yourself, seeing the annointed image of God in your neighbor. The second, lasting self-control, is pulling the plank out of our own eyes before taking the splinter out of our neighbor's eye. It must be lasting - like the alcoholic realizing he is an alcoholic must take steps against his disease and refrain, for the rest of his life, from drinking. So too the person wanting to conquer this barbarism must act upon love, realize he has been bought at a great price, and continually control himself from acting contrary to this love.

The serpent of our tribal barbarian, loathsome, close to the earth, inhuman in its reptilian coldness, has to be conquered by the eagle of our political self, immortal, autonomous, angelic. Only this conquering of the serpent in us, this movement out of darkness to light, from earth bound slavery in sin to the freedom of the new dawn, only this is a solution to what otherwise would prove a lasting servitude of horror and blood. This remarkable insight on the part of Aeschylus at the dawn of the Golden Age of Athens, even if it didn't take root in the Athens that was eventually defeated by Sparta at the end of the Polyponnesian war, nevertheless paved the way for the greater and more powerful mythology that was to dominate Europe for over 2000 years, which was to alter the course of Western Civilization from barbaric tribal roots to civilized political cultures, which even now seems the only solution to the problem of perpetual bloodshed and retribution.

Facile the descent to where no birds live; Night and day the dark gates of the Unchanged; But to recover the stair and ascend toward the sweet light, This is the work, this the labor. - Aeneid 6.124

Tuesday, December 1, 2009

Fagles and the Closed Circle

Friday, November 20, 2009

Joker's Origin Speeches

The Joker [holding a knife inside Gambol's mouth]: Wanna know how I got these scars? My father was... a drinker. And a fiend. And one night he goes off crazier than usual. Mommy gets the kitchen knife to defend herself. He doesn't like that. Not-one-bit. So - me watching - he takes the knife to her, laughing while he does it! Turns to me, and he says, "why so serious, son?" Comes at me with the knife... "Why so serious?" He sticks the blade in my mouth... "Let's put a smile on that face!" And... [looks sidelong at Gambol's thug, watching the whole thing in horror] Why so serious?

Second:

The Joker: Well, you look nervous. Is it the scars? You want to know how I got 'em? [He grabs Rachel's head and positions the knife by her mouth] Come here. Hey! Look at me. So I had a wife, beautiful, like you, who tells me I worry too much. Who tells me I ought to smile more. Who gambles and gets in deep with the sharks... Look at me! One day, they carve her face. And we have no money for surgeries. She can't take it. I just want to see her smile again, hm? I just want her to know that I don't care about the scars. So... I stick a razor in my mouth and do this... [the Joker mimics slicing his mouth open with his tongue] ...to myself. And you know what? She can't stand the sight of me! She leaves. Now I see the funny side. Now I'm always smiling!

Both speeches tell tales of human cruelty and horror. The first is specifically catered to Gambol. It speaks of a father's cruelty to his son - beating of a mother, and the son attempts to stop the violence only to be maimed cruelly for trying to step in. This vision of broken homes, drunken fathers, abused mothers seems to be the plague of many homes within the black community. Our current culture registers thousands of situations like this one and the despair that festers due to witnessing such horror leads to violence and more violence. The very act of nobility, stepping in to stop the drunken father, is made into something futile and foolish. Who, after all, would attempt nobility against such overwhelming evil? Who would be brave enough to stop the evil rather than becoming evil himself? Surely the only way to survive in such a horrific world of violence is to become a monster just like daddy. This is the implication of Joker's speech to Gambol, a man who has turned to crime and violence and thus can never live a normal life of peace and love amidst his family. But the speech also is geared towards the henchmen and the audience. You see how good men are maimed? You see how even powerful men like Gambol are swallowed up by hungrier monsters like the Joker? Look upon my works you mighty and despair.

Both speeches tell tales of human cruelty and horror. The first is specifically catered to Gambol. It speaks of a father's cruelty to his son - beating of a mother, and the son attempts to stop the violence only to be maimed cruelly for trying to step in. This vision of broken homes, drunken fathers, abused mothers seems to be the plague of many homes within the black community. Our current culture registers thousands of situations like this one and the despair that festers due to witnessing such horror leads to violence and more violence. The very act of nobility, stepping in to stop the drunken father, is made into something futile and foolish. Who, after all, would attempt nobility against such overwhelming evil? Who would be brave enough to stop the evil rather than becoming evil himself? Surely the only way to survive in such a horrific world of violence is to become a monster just like daddy. This is the implication of Joker's speech to Gambol, a man who has turned to crime and violence and thus can never live a normal life of peace and love amidst his family. But the speech also is geared towards the henchmen and the audience. You see how good men are maimed? You see how even powerful men like Gambol are swallowed up by hungrier monsters like the Joker? Look upon my works you mighty and despair.The second speech is similarly geared to Rachel. Little is known about Rachel's character except that she is a hard-headed woman making it in a man's world. She is tough, persistent, courageous and an ardent follower of justice. Having chosen such a life how can she risk the vulnerability of being in love? Her very noble choice of pursuing a career in law precludes the possibility that she ever have a loving family relationship. When Joker describes a husband/wife relationship with a despairing wife who has been pummelled by a cruel masculine world he is describing the possible world Rachel would experience were she to ever slip and let herself fall in love. Moreover, his maiming of himself (allegedly) represents the despair that the wife would experience which knows no remedy but more despair; a self-sacrificing husband whose very act of self-sacrifice causes only more sorrow. What else could a woman like Rachel expect but that the beautiful man she loves be tortured and maimed by the world? What else could she expect but that "the sharks" would come for them both eventually?

The really great depth of this version of the Joker is that he isn't just a maniac who blows things up or randomly kills people (like Jack Nicholson's character) nor is he just a silly wisecracker out to give grief to the guy in the grey tights (like Cesar Romero's character). Instead he is the psychologically dangerous character of the greater Batman graphic novels; he is the Nietzschean ubermensch, the Machiavellian prince, the character who is beyond the realm of right and wrong who worms his way into our subconscious with questions, suggestions and doubts. In short, he is the worst villain of the modern world b/c he can invade and infect any person anywhere, creating chaos that erupts in the despairing psychology that later manifests as violent action against others. He creates human time bombs using nothing more than words.

The really great depth of this version of the Joker is that he isn't just a maniac who blows things up or randomly kills people (like Jack Nicholson's character) nor is he just a silly wisecracker out to give grief to the guy in the grey tights (like Cesar Romero's character). Instead he is the psychologically dangerous character of the greater Batman graphic novels; he is the Nietzschean ubermensch, the Machiavellian prince, the character who is beyond the realm of right and wrong who worms his way into our subconscious with questions, suggestions and doubts. In short, he is the worst villain of the modern world b/c he can invade and infect any person anywhere, creating chaos that erupts in the despairing psychology that later manifests as violent action against others. He creates human time bombs using nothing more than words.The two speeches also are conversely to male and female figures - thus to all people. A masculine story of father dominance, like Saturn devouring his children, for the young boy in Gambol. And for the little girl in Rachel, a feminine story of loss and sorrow, like Niobe or Rachel mourning and weeping because they are nought. The futility of power that emasculates the male; the helplessness of weakness that crushes the female. Adam's curse of "earning his bread by the sweat of his brow"; Eve's curse of "bearing her children in pain". Joker is the universal Satan in this instance and like Satan he breeds amongst his victims intense despair in the face of his irresistable evil.

Friday, November 13, 2009

Friday the 13th Post

When, in disgust with Fortune and men's eyes,

I all alone berate my aching pate,

And trouble deaf woodwork with my bootless cries,

And look upon myself and curse my fate.

When this one's a clod and this one's a dope,

A scalawag, a nincompoop, a tart,

When pimps are praised and whores are full of hope,

And all high thought is edifice and art,

Then in these thoughts my mind as black as night,

I bang my fist and rail against the grey,

(though silently for fear might children fright;

Or solid men in coats might take me away)

What good is rage the only wealth it brings;

Destruction, sorrow, cabbages and kings.

I rewrote it some.

Wednesday, November 11, 2009

Thoughts on Iliad

On the Iliad:

1st

Achilles is spiritually blind.

Oedipus is spiritually blind.

Achilles has a, um, interesting relationship with Thetis, his mom.

Oediups has a, um, interesting relationship with his mom.

Achilles father, Peleus, is absent from the epic, spoken of only when asking if he is dead.

Oedipus has killed his father.

Achilles has a spiritual awakening only after an intense experience of pain and loss.

Oedipus has a spiritual awakening only after an intense experience of pain and loss.

So is Achilles another Oedipus? Was Homer aware of the myth? Or is Oedipus Achilles? Was Sophocles aware of the epic?

******

2nd

Briseis mourns over Patroclus' body in book 19 saying that the dead man was gentle and good to her; "you were always kind."

Helen mourns over Hector's body in book 24 (the last of three female mourners, Andromache and Hecabe, and the penultimate human voice in the epic poem) saying that the dead man was always gentle and good to her; "you with your gentle words and your gentle ways"

Both are slaves; both are left utterly alone at the end of the work (Helen b/c she lives with a lout and Briseis b/c Achilles soon will be dead).

Both are mourning over the "good man" character who is now dead.

Both are mourning over the Achilles duplicate (Patroclus and Hector connected by the wearing of the armor)

**********

3rd

Homer makes the gods look ridiculous, undermines them, shows that they are not worthy of worhsip - but some of the humans who fail and die are. Homer elevates the humans to a position superior to the gods.

Why does he do this?

Hypothesis: He does this to

1. show that screwing up in life is not the worst thing possible

a. with perfect, unyielding and aloof gods who cannot experience the human condition the standard to which we hold ourselves makes us psychotic and homicidal (or suicidal)

2. smash the hold that the priesthood had on the lives of laypeople

a. a priesthood beholden to perfect gods would have held that perfection over laypeople like a cult or cabalistic master/slave relation

b. much like the scribes and Pharisees

c. Christ does later what Homer does here.

3. force the reader to find new gods (or god)

a. if these gods, these passions, are not to be worshipped as the God then who is? Deus ubi est?

Sonnet 116 (a blog for Ben)

- Let me not to the marriage of true minds

- Admit impediments, love is not love

- Which alters when it alteration finds,

- Or bends with the remover to remove.

- O no, it is an ever-fixed mark

- That looks on tempests and is never shaken;

- It is the star to every wand'ring bark,

- Whose worth's unknown, although his height be taken.

- Love's not Time's fool, though rosy lips and cheeks

- Within his bending sickle's compass come,

- Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks,

- But bears it out even to the edge of doom:

- If this be error and upon me proved,

- I never writ, nor no man ever loved.

(William Shakespeare)

I agree that one reading of the poem is an honest analysis of true love. Unfortunately, I have never found a passage of Shakespeare that is entirely honest; he is always wearing a mask and always has something up his sleeve. Consequently, this poem, which seems like a straightforward proclamation of the steadfastness of love probably is too good to be true. He does the same thing in Romeo & Juliet, offering what looks like a great romance but loaded with problems that indicate the opposite of real love. Here there are numerous ambiguities, subtle references, and structural alterations that indicate if nothing else a difficulty in the poem.

First, the English sonnet normally has in the third quatrain a complication of the subject introduced in the first two quatrains. What is the complication? There is none (apparently) - not even in the last bit of the poem. The normal indicator of complication "but" is in the 12th line at the end of the third quatrain. If the turn exists at the beginnig of the third quatrain then our complication of the discourse is that Love is not Time's fool - which means what? The Fool was subordinate to the King so that Love is the King and Time is the fool (instead of the other way around). But Shakespeare who wrote this poem also wrote "King Lear" - a tragic play in which the King, Lear, is imprisoned by his daughters for being foolish in his actions and the Fool is seen as far more free and wise than the king. Moreover, during the play King and Fool trade places and so represent the same thing in different postures. If this is so (and to an audience familiar with Lear it seems to be an intentional comparison) is the comparison supposed to be between the foolishness of Love and the kingliness of Time? Does Time rule over us? Is Love a foolish thing (b/c it certainly does make men foolish as Mercutio says and Iago attests)? Or are Love and Time the same thing?

Second, there is a frequent ambiguity to the use of pronouns; the "it" in lines 2,4&6 seemingly references to "love". But then what is the antecedent of "his" in line 7,9&10 ? The Star? Love? Time? If the "his" in 7 refers to the Polar Star then the worth of the star is unknown but his height is taken; meaning, we can measure the thing empirically but don't actually know what it is worth. Thus the Pole Star's attributes are identical to Love's and the "his" could reference either. If the "his" in 10 refers to "Time" that makes sense - but the ambiguity suggests that the sickle belongs to Love. Same with the "his" in 11 which seems to refer to Time since "brief hours and weeks" is the auspice of Time. But Love too is brief so the line could mean that Love does change in the short time we know of it on earth. This ambiguity is particularly pointed in the 12th line where the antecedent of "it" is completely obscure. What is born out to the edge of doom? Love? Time? It?

Finally, Shakespeare is a master of the language. Nowhere else in his corpus of works is there ever so seemingly straightforward and honest a proclamation. Also, nowhere else are there so many ambiguities, vagueries, mistakes and errors. Consequently, the last couplet can be read in two different ways.

If this be error and upon me proved,

What is the "this" to which he refers? The proclamation of love? The construct of the poem prior? the language itself? If it is the proclamation of love he has suggested hitherto that love doesn't ever change; that it is constant; that it looks upon the tumult of human life from a remote and aloof position similar to a star looking down upon earth. But this isn't right about love and Shakespeare knew it. Human love isn't constant as he proved in "Much Ado About Nothing" and "The Merchant of Venice" and "Romeo & Juliet" and "Othello" and numerous other works. Moreover, if he is referring to Love as a god or The God he seems to be describe an aloof and impersonal god that remains utterly unmoved by the sorrows and passions of human existence. But his whole religion of Incarnation, redemption, suffering and resurrection speaks contrary to this. Even if he is correct in assessing human love and divine love as unchanging and inflexible he would be well aware of the maxim that living things alter and change and dead things don't. Consequently the love he is describing isn't truly living but dead. Is he in error here? Is this the "this" to which he refers in line 13? If the "this" is the construct of the poem, it has already been shown that structurally the poem doesn't follow the normal modus operandi of a sonnet. There is no apparent complication, there is no consistent poetic conceit, there are numerous switches in the rhythmic pattern during the poem. So the poem is itself somewhat in error. The language is intentionally ambiguous and hard to fathom; it too is in error. The "this" is, consequently, proven to be in error.

Given this proof, the line "I never writ, nor no man ever loved" adopts a knew meaning. Is "I never writ" an excuse? An escape? A Thomistic "burn it; it's all straw" statement? And has anyone ever really loved? Do we really know what love is? Do we really want to know what love is? Or do we only think we know what love is and desire love as long as it makes us feel good and gives us pleasure? Complicated. Brilliant.

Wednesday, October 21, 2009

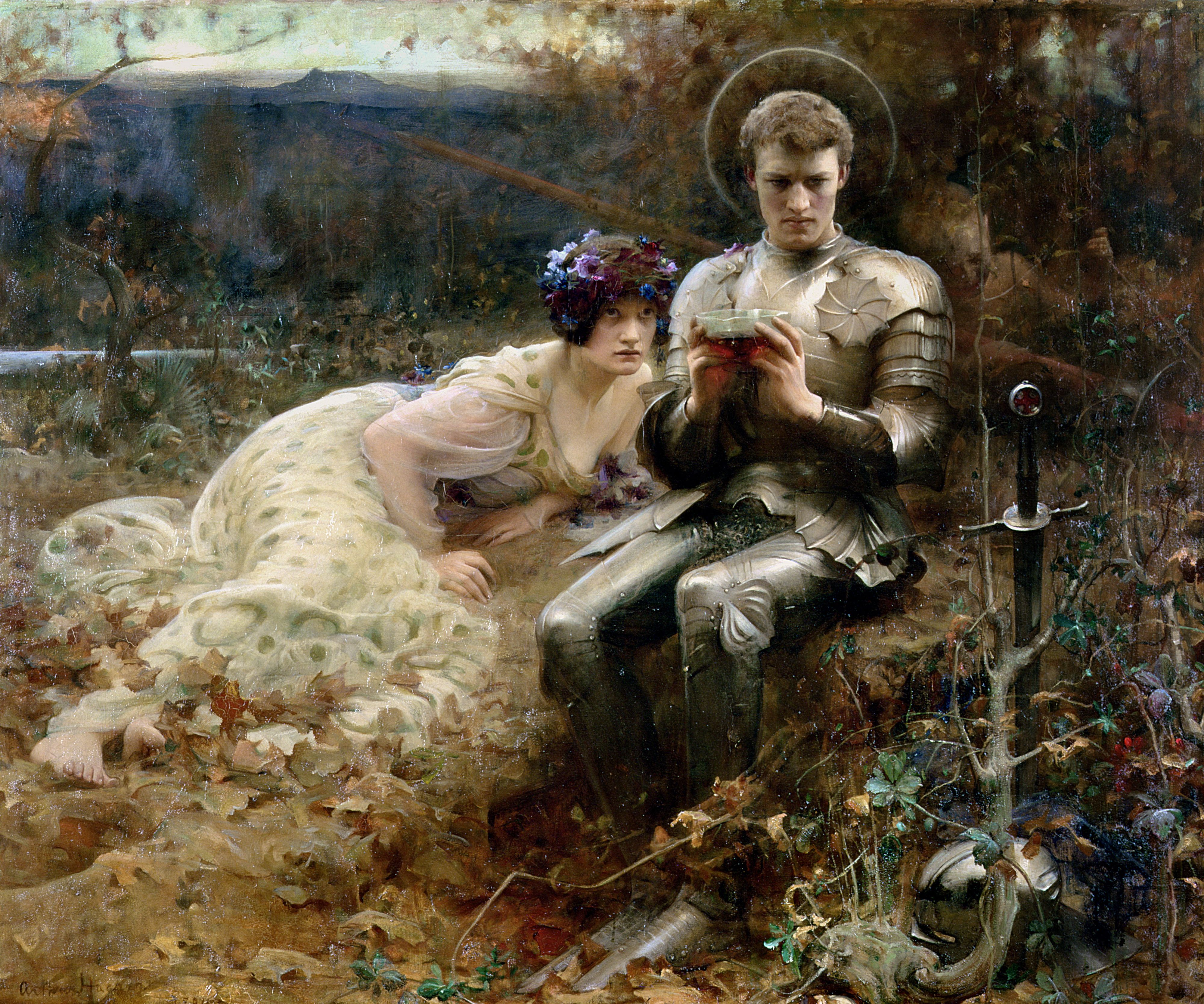

Malory's Grail Imagery

But why a drinking cup? Drinking, like eating, is central to human life and the preservation of human life but is also symbolic of taking into ourselves ideas and ways of thinking. Thus Adam and Eve when they transgress the law do so through eating of a fruit. Thus also Yahweh institutes a Passover Feast marking the freedom from bondage in Egypt. Thus also Christ institutes the Last Supper/Eucharistic Feast. So the Grail has something to do with taking into ourselves some nourishment spiritually, intellectually, emotionally.

Most commentators associate the Grail with Jesus and the finding of the Grail as seeing God in the beatific vision. It is a “vision of heaven”. But this raises problems in the Malory story wherein first the Grail is associated with Christ and the theophanic imagery that is pertinent to him, but also is associated with women who always seem to accompany the Grail to some degree. Second, though the finding of the Grail is accomplished by Galahad, Malory’s story neither makes him the most intriguing character nor does the story end with Galahad’s ascension into heaven. Instead, Malory’s story continues with the civil war, the loss of Camelot and death of Arthur, and the misfortunes of Arthur’s greatest knight, Lancelot. Consequently there seems to be more to the story of the Grail then merely seeing heaven.

Most commentators associate the Grail with Jesus and the finding of the Grail as seeing God in the beatific vision. It is a “vision of heaven”. But this raises problems in the Malory story wherein first the Grail is associated with Christ and the theophanic imagery that is pertinent to him, but also is associated with women who always seem to accompany the Grail to some degree. Second, though the finding of the Grail is accomplished by Galahad, Malory’s story neither makes him the most intriguing character nor does the story end with Galahad’s ascension into heaven. Instead, Malory’s story continues with the civil war, the loss of Camelot and death of Arthur, and the misfortunes of Arthur’s greatest knight, Lancelot. Consequently there seems to be more to the story of the Grail then merely seeing heaven. Technically the Grail image, or Graal, was originally a dish or mixing bowl and comes from Celtic mythology where it was a cauldron owned by the Sea Lord, Mannannan son of Llyrr. This cauldron, overflowing with wine and food, was kept in the Domnu, the deep sea or abyss, in the land of the Fomorians, the giants under the sea and was a cup of rebirth, renewal and inspiration. Three drops from this cup transformed Gwion Bach into Taliessin, the great poet of Gaelic mythology. The Graal stands as a metaphor, then, for that source in the subconscious amidst the giants of nightmare and dreams which pours forth the inexhaustible images, ideas, and forms that inform the waking world. Finding the Grail is finding the source of these dreams.

Furthermore, the cup is a drinking cup from which pours forth water and wine (just as water and wine issued forth from the side of Christ on the Cross). This birth image consists of a mixture of two complementary elements. Water represents purity and whiteness, the ocean, the feminine powers of the subconscious and the body itself. Wine represents fire and heat, blood, and the sun. It is associated with the color red (and one recalls here the image in Malory of the red and white dragons that contend with each other over the land of Vortigern). Wine also represents the conscious realm of the mind. But the mixture of the two is what is important within the cauldron of the Grail.

Man consists of a metaphysical, immortal, divine element (the mind) and a physical, mortal, human element (the body). Most people consider that the metaphysical is superior, good, pure, and needs to be pursued while the physical body is thought of as bad, corrupt, inferior and needs to be punished or completely abandoned. The Cathars went so far as to help others release from this mortal coil by galloping about Southern France killing them. Even today, heretical sects in certain religions consider this world to be illusion and the greater glory to be in the next world; and they are willing to bet their body and the bodies of others against the promise of 72 virgins (or grapes).

There are also some people who completely deny the metaphysical realm and claim that all we have is the physical world of the body. Pleasure, indulgence, and power are the only claims to greatness one can make with such a vision.

But this schizophrenic way of looking at our existence is a warped vision. What the Grail image seems to suggest is that the good lies not in the next life but in this one; in a union or marriage between the metaphysical and physical worlds. In this sense the marriage to a good woman is the Grail. In this sense seeing heaven as the acquisition of a sense of balance or perfection is the Grail. In this sense Mary (or Elaine for Lancelot) is the Grail. The Grail, the sense of balance between these two halves of the red dragon and the white dragon is itself that peace with passeth (or is greater than) understanding which when made permanent we call secure, or salvation. It is a state of consciousness operating out of complete harmony within oneself and out of which one perceives the unity of all things.

Our hearts were made for this God and they are restless until they find their rest in Him.

The Grail represents the acquisition of harmonious balance with ourselves, the source of our being, out of which is born (with blood and water) the Church of ideas, images, actions, words, and love.

Friday, October 16, 2009

On Mythology

A new series of discussions up at YouTube.

Thursday, October 8, 2009

Oedipus and Human Life

The play Oedipus Rex by Sophocles certainly seems to embody the change and alteration held by the ancient world to be the heart of religious experience. But Oedipus also seems to undergo a certain experience of the stages of life as well. Consequently, the play can be taken as a metaphor for entering into that initiated world of self-reflection.The original Sphinxian question of four legs, two legs, three legs gives the stages of man in a protean, riddling fashion. Indeed there are eight stages to human life, paralleling the eight notes of the octave in music.

The play Oedipus Rex by Sophocles certainly seems to embody the change and alteration held by the ancient world to be the heart of religious experience. But Oedipus also seems to undergo a certain experience of the stages of life as well. Consequently, the play can be taken as a metaphor for entering into that initiated world of self-reflection.The original Sphinxian question of four legs, two legs, three legs gives the stages of man in a protean, riddling fashion. Indeed there are eight stages to human life, paralleling the eight notes of the octave in music.

The Ages of Man

- Ut: Birth

- Re: Infancy

- Mi: Youth

- Fa: Adulthood

- Sol: Initiate

- La: Adept

- San: Master

- Ut: Death (which is a second birth)

Oedipus suggests that he meets with Laius (his father and king of Thebes) at a place where three roads meet. This meeting at the triskelion in which Oedipus kills the old man represents the meeting of the young adult with the "father figure" of imposed rule or law in his life. Somewhere that three roads meet we encounter the other – the father figure of imposed laws – and we kill it, rebel, and do our own thing – and immediately we engage in the pull of the earth, the way of all flesh, becoming wedded to our mother in the feminine powers of the natural self. Only when we come awake to the horrors of our own life, the pain we inflict, the suffering we have caused, do we actually gain eyes to really see what we are. For the first time we encounter ourselves and it blinds us, dazzles us, terrifies and sets us on a new path of discovery and discovery and discovery; one encounter with The Other after another equaling eight total encounters in spirallic path of repetitions.

But when that which is perfect is come, then that which is in part shall be done away. When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things. For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known. And now abideth faith, hope, charity, these three; but the greatest of these is charity.

But when that which is perfect is come, then that which is in part shall be done away. When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things. For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known. And now abideth faith, hope, charity, these three; but the greatest of these is charity.- St. Paul

1 Corinthians 13

Jaques:

All the world's a stage,

My heart leaps up when I behold

My heart leaps up when I behold

A rainbow in the sky

So was it when my life began;

So is it now I am a man;

So be it when I shall grow old,

Or let me die!

The Child is father of the Man;

I could wish my days to be

Bound each to each by natural piety.

- William Wordsworth. 1770–1850

The Rainbow

Verily, verily, I say unto thee, When thou wast young, thou girdest thyself, and walkedst whither thou wouldest: but when thou shalt be old, thou shalt stretch forth thy hands, and another shall gird thee, and carry thee whither thou wouldest not.

Verily, verily, I say unto thee, When thou wast young, thou girdest thyself, and walkedst whither thou wouldest: but when thou shalt be old, thou shalt stretch forth thy hands, and another shall gird thee, and carry thee whither thou wouldest not.

The pill and real men

Taking the pill for past 40 years 'has put women off masculine men'

Read more: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-1218808/Contraceptive-pill-women-attracted-masculine-men--interested-boyish-looks.html#ixzz0TMStYlaU

Monday, September 21, 2009

A bit of Isopsephia

It occurs 5,410 times in the Bible, being divided among the books as follows: Genesis 153 times, Exodus 364, Leviticus 285, Numbers 387, Deuteronomy 230 (total in Torah 1,419); Joshua 170, Judges 158, Samuel 423, Kings 467, Isaiah 367, Jeremiah 555, Ezekiel 211, Minor Prophets 345 (total in Prophets 2,696); Psalms 645, Proverbs 87, Job 31, Ruth 16, Lamentations 32, Daniel 7, Ezra-Nehemiah 31, Chronicles 446 (total in Hagiographa 1,295).

So sacred was it that Jews would not utter it aloud after a certain era and substituted the name "Adonai" and "Jehovah" instead:

The true name of God was uttered only during worship in the Temple, in which the people were alone; and in the course of the services on the Day of Atonement the high priest pronounced the Sacred Name ten times.

A Jewish audience, familiar with that four letter formula would have recognized it when it showed up in literary isopsephia, the use of letters corresponding to numbers corresponding to concepts in religious literature.

A Jewish audience, familiar with that four letter formula would have recognized it when it showed up in literary isopsephia, the use of letters corresponding to numbers corresponding to concepts in religious literature.The question then arises, if by the time of the crucifixion the utterance of the tetragrammaton was forbidden, wouldn't the Jewish crowd have recognized it and been incensed (in a bad way)? Wouldn't they riot against the Romans for committing such a blasphemy?

Matthew records no response from the Jews:

And sitting down they watched him there; And set up over his head his accusation written, THIS IS JESUS THE KING OF THE JEWS. Then were there two thieves crucified with him, one on the right hand, and another on the left.

Nor does Mark:

Nor does Mark:And it was the third hour, and they crucified him. And the superscription of his accusation was written over, THE KING OF THE JEWS. And with him they crucify two thieves; the one on his right hand, and the other on his left.

Nor does Luke:

And saying, If thou be the king of the Jews, save thyself. And a superscription also was written over him in letters of Greek, and Latin, and Hebrew, THIS IS THE KING OF THE JEWS. And one of the malefactors which were hanged railed on him, saying, If thou be Christ, save thyself and us.

Only John, the Greek-inspired isopsephiaist, recounts any response from the crowd to this action:

Where they crucified him, and two other with him, on either side one, and Jesus in the midst. And Pilate wrote a title, and put it on the cross. And the writing was JESUS OF NAZARETH THE KING OF THE JEWS. This title then read many of the Jews: for the place where Jesus was crucified was nigh to the city: and it was written in Hebrew, and Greek, and Latin. Then said the chief priests of the Jews to Pilate, "Write not, The King of the Jews; but that he said, I am King of the Jews." Pilate answered, "What I have written I have written."

Where they crucified him, and two other with him, on either side one, and Jesus in the midst. And Pilate wrote a title, and put it on the cross. And the writing was JESUS OF NAZARETH THE KING OF THE JEWS. This title then read many of the Jews: for the place where Jesus was crucified was nigh to the city: and it was written in Hebrew, and Greek, and Latin. Then said the chief priests of the Jews to Pilate, "Write not, The King of the Jews; but that he said, I am King of the Jews." Pilate answered, "What I have written I have written." The response of "take that down - you should not have written it" seems mild in comparison to the severity of the blasphemy. Additionally, John is a later writer, c. 90-100 and was writing for Greeks and lapsed Jews. So the response of his gospels was, probably, his own addition since it doesn't appear in the other three earlier works. Moreover, look at Pilate's response in this gospel; "What I have written I have written," in Greek "απεκριθη ο πιλατος ο γεγραφα γεγραφα"

A strange formula. Christ himself, though, was the LOGOS, the word made flesh. Does "written" here have another meaning? Written versus spoken word? Set down permanently on paper or wood like a man nailed to a cross? The living word of the LOGOS speech vs. the (soon to be) dead word of writing? (very Platonic that) We have to write it down if we are to remember it, right? But the minute we do don't we lose the power of life that is in the thought/word/speech? We have only a patient etherized upon a table not Lincoln in full force at Gettysburg. We have three lumps of stone in the morning sun and not three terrifying trolls. So is the whole of the crucifixion somethin of an injunction against mistaking the dead written word for the living reality?

Interesting also to note in John that the INRI inscription appears at 19:19 "εγραψεν δε και τιτλον ο πιλατος και εθηκεν επι του σταυρου ην δε γεγραμμενον ιησους ο ναζωραιος ο βασιλευς των ιουδαιων". (emphasis mine - nota bene "grammenon" as in "tetragrammaton") That's no big deal, except it would have been a big deal to John and his audience b/c 19 is 18+1 or 6+6+6+1 or 6661. Again, no big deal until we realize that this "number of the beast" is part of a calculation involving 6 (the number of rational thought) elevated three times (the number of perfection) plus 1 (the number of unity and wholeness) which corresponds to the risen Lord.

My ability with this is very poor, but INRI connected to YHVH would have sparked in the mind's of John (and the other writers) and his audience a connection that was surely unavoidable. How they worked this connection into their writings is a remarkable bit of artistry.

Friday, September 18, 2009

Rome

Enjoy!

Thursday, September 17, 2009

Beowulf performed

I love a great performance of a great work.

Here first is Benjamin Bagby of the group Sequentia performing in Old English accompanying himself with a lyre.

Friday, September 11, 2009

Eight Years Ago Today

Wednesday, September 2, 2009

Tolkien : His Genius

The genius of J.R.R. Tolkien seems often overlooked when referring to his "children's story" of The Hobbit. The story, however, reveals powerful depth of thought and construction. Tolkien was very familiar with dragons and dragon imagery saying of his own youth that he once sought to encounter a dragon; "I desired dragons with a profound desire." After the Somme he undoubtedly lost such a desire. However, Tolkien seems to intimate in his work that the encounter with a dragon is actually an encounter with oneself; the anagogical level of self-reflection that reveals a man to himself.

But Tolkien seems to employ the imagery to an even greater level. His dragon imagery embodies the action of self-reflection that emerges in serious intellectual inquiry. The essential questions of "Who am I?" "What am I about?" "What am I capable of?" lie at the heart of the spiritual quest to know ourselves. Consequently, the pattern of the Hobbit, which is itself a spiritual journey of self-discovery, displays this mirror doubling in its imagery.

The visiting of the beneficent high elves in Rivendell in which Thorin and company are the voluntary guests of Elrond is mirrored by the "visiting" of the hostile wood elves in Mirkwood in which the company are involuntary guests of Thranduil. Rivendell is a place of joy and light, rest after their encounter with the trolls. The wood elves are a place of darkness and treacherously alluring bounty which imprisons the company. Both are representative of the capacity for creative thought; the first in its benevolent form of comedy, the second in its malevolent form of tragedy. Bilbo leaves from the first riding on ponies and escapes from the second riding on barrels; a fact that later will confuse Smaug and help to save Bilbo.

Pathetic.

Tuesday, September 1, 2009

Down into the cave

Thursday, August 27, 2009

On the Liberal Arts

Applications to Colleges Such as St. John's Are Dropping As the Downturn Leads Families to Weigh the Value, And Price, of a Liberal Arts Degree More Carefully.

This article is from today's Washington Post (August 27. 2009):

I certainly understand the struggle of LA education in this sort of environment. Unfortunately, I think that they are fighting a losing battle when they claim that a LA education is “practical” and gives “tools for life”. I don’t know if that is correct and I don’t think it is a selling point. It’s much like University of Dallas trying to field a baseball team to compete with Texas Tech or SMU – ain’t gonna happen.

More to the point, though, I still am unconvinced that the praxis of liberal arts education is that strong. Praxis always speaks to utility, practicality, what are you gonna “do with” that degree in (insert LA field here)? When it comes down to it, LA education is impractical b/c it encourages the mind/soul/nous to pursue beauty, goodness, truth with ardor – not to use verum bonum pulchrum for some practical end. Such pursuit and contemplation ultimately is liberating; makes the freeman out of the slave, b/c it broadens the mind to see vaster vistas than before.

But liberation, though one of the main goals of the education, can’t actually succeed unless the student pursues knowledge with abandonment of any practical return; a certain ecstasy of sorts has to happen.

Therefore, I think LA education is as impractical as love.

Though it isn’t a big selling point to say “we offer an utterly impractical course of study” – ne’theless, if we make the modus operandi for study a praxis we have debased the finest and noblest of pursuits into something base and selfish; just as if we attribute to love a selfish motive, the promise of gain or some irresistible drive of biology we no longer have love, merely a weaker form of power.

Monday, August 3, 2009

An exchange - "Rope" and Dostoevsky

One of my colleagues sent me this note:

Hello colleagues,

I hope you are all having a good summer.

But I also hope one or more of you will be eager to apply your critical thinking and answer some of my questions regarding the following argument for atheism. The argument at the link below was sent to me by an alum – this is an article that is currently influencing his choosing atheism.

http://www.infidels.org/library/modern/raymond_bradley/moral.html

I am hoping one of you will volunteer to read this article and spend 30-60 minutes talking with me about it. I have some ideas about critiquing this argument – but as I am neither a theologian nor philosopher I would like to bounce my thoughts off of one of you and hear your response as well.

Thanks

Me: To misquote Jerry Maguire, Mr. Bradley lost me with "hello." In this opening paragraph he states:

First: there is ample precedent for what I am doing. Socrates, for example, examined the religious beliefs of his contemporaries--especially the belief that we ought to do what the gods command--and showed them to be both ill-founded and conceptually confused.

-no, he didn't. What he did was to shake the pharisaical complacency and self-righteousness of his contemporaries in order to deepen their understanding of their religious world. If we're to call Socrates (and Plato) anything it would not be "irreligious" and it certainly would not be "atheist". Why so many atheists turn to Plato for solace is utterly beyond me.

I wish to follow in his footsteps though not to share in his fate. A glass of wine, not of poison, would be my preferred reward. (coward)

FURTHER, he misunderstands the Dostoyevsky argument when he says:

"If there is no God, all things are permitted." So said one of Dostoyevsky's characters in Crime and Punishment. He was claiming that if God does not exist, then moral values would be a purely subjective matter to be determined by the whims of individuals or by counting heads in the social groups to which they belong; or perhaps even that moral values would be totally illusory and moral nihilism would prevail. In short--the argument goes--if there are objective moral truths, then God must exist.

No. That's not it at all. The argument Dostoyevsky is making is that if we abandon the reality of God (or even of gods) then there are no restrictions upon our actions and being a murderer is as valid as being a saint.

The actual passage is in Book 11, chapter 4 of Brothers K and consists of an exchange btwn Smerdyakov and Ivan Karamazov recounted by the increasingly insane Ivan to his brother, Alyosha. Here is the text:

"But what will become of men then?’ I asked him, ‘without God and immortal life? All things are lawful then, they can do what they like?’ ‘Didn’t you know?’ he said laughing, ‘a clever man can do what he likes,’ he said. ‘A clever man knows his way about, but you’ve put your foot in it, committing a murder, and now you are rotting in prison.’

Smerdyakov has just murdered a man and claims that Ivan is complicit in the murder b/c it was he that told Smerdyakov that men can do what they will w/o God. (See Hitchcock's "Rope") So in Dostoevsky's portrayal, the original idea professed by Ivan becomes the catalyst which justifies the murderous Smerdyakov in his actions!!!! It isn't a proof of the existence of God, it is a proof of the murderousness of human nature without God.

I never cease to be amazed by the ignorance of history that would claim that religion has been the cause of all our agony rather than that religion has been the one bulwark against the tide of war, famine, suffering and cruelty that inundates our miserable little race. That just isn't so, and Dostoevsky, on the eve of one of the bloodiest centuries in all of human history, was crying out against the abandonment of the one thing that might stem the blood dimmed tide and preserve the ceremony of innocence.

Finally, though, I dismiss the argument in the following way. I don't have time to read and refute all these arguments, I've read them before, thought them before, experienced each of them before. But if there is to be any argument about anything we have to first agree that argument, reason, logic, are fitted to a reality that exists. When we argue we argue about something. When we use language it is language about something. If nothing else, when we say "God" we mean this correspondence. Belief in the reality of that which we argue about allows argument itself. Belief in the reality to which language has correspondence allows language itself. Mr. Bradley argues there is no God.

If we agree with that argument then Mr. Bradley is no more right than Mr. Chesterton or Mr. Lewis or Mr. Pascal or Mr. Saint John and the only principle upon which we can rest any discussion is the triumph of my will over his or his will over mine.

I choose my will ... which dictates that his argument is trash.

End of discussion.

Here's "Rope":

Friday, July 31, 2009

Value, Meaning and the Economic Crisis

Wednesday, July 22, 2009

A discussion on teaching

************************************

He asks: As for advice,anything you can send my way would be great. I'm not even sure what questions to ask.

Respondeo ad eum: well, let me ask a few questions then:

1. what subject(s) are you teaching?

2. what age group?

3. where are you going to be teaching?

************************************

He asks: I guess my first question is what do you do differently from other teachers that makes you more successful or helps your students succeed to a greater degree?

Respondeo ad eum: first, I don't really follow any of that education classes BS like rubrics and week planners and teaching to different styles of learning. Partly b/c I'm no good at it, partly b/c it doesn't really seem to help in the long run. I little planning, yes, clear & simple expectations for student achievement, yes, organizing activities other than purely lecture, yes. I have a colleague who thinks that piling on oodles of terms and reading and lab work will help students love and learn the subject. Not true. An appropriate amount of work (with constant readjustment to what is reasonable) but not piles of backbreaking labor.

second, constant interpretation of texts, clarification, explaining things so that students can understand the material. discussion of the material. working through in discussion why the arguments are important.

third, I give only a few major terms that need to be known and repeat them, and repeat them, and repeat them. Other minor terms are thrown about during lectures and discussions, but the major terms (10 or so) are reiterated during the course of the year.

finally, I never pander to students. I've always treated students as though they were bright enough to understand the importance of what was put before them and important enough to put before them the best and most powerful stuff.

************************

He asks: Is it your passion for the subject, a passion for your students succeeding, both?

Respondeo ad eum: Both, really. I love what I teach and love whom I teach. The subject matter must be interesting to me or I can't teach it. Consequently if I have to teach something that I am not familiar with I always try to find the angle, the point of interest, something in it that I find remarkable - never teach something b/c you have to - always teach it because you have come to want to. I'm always being told "you have to love these students more" but as one of my colleagues pointed out we can only love our students to the degree that they are in our classrooms. Genuine interest in their success is important, though never to the point of sacrificing the curriculum - they need to know this stuff & to not teach it is actually doing them a disservice. But I know many teachers who love their subject matter and can't stand the students they teach; even going so far as to say that the students are idiots or that it's their fault they can't learn. Though it is sometimes their fault, if they don't understand the material I ought to make an effort to help and not berate them. Above all, compassion and mercy. I only hold a student's feet to the flames if I think it will help him/her, never just to exert my vindictive desires.

************************

Respondeo ad eum: Lastly, if there is any advice that I would offer gratis, I would quote one of my great mentors/teachers who said "we don't try to save every student we teach, but we do try to offer them the tools to handle salvation when it comes to them." I think that, bottom line, this is what I do (or try to do). Teaching is not about just conveying information (b/c YouTube alone would be good for that), nor is it about simply giving skills (b/c that would be found in a tech school), nor is it about saving the souls of your students (thank God, b/c I would suck at that royally!). Ultimately teaching is about training students to be able to handle the difficult choices, decisions, thoughts that will come to them. I hold this mantra for every discipline whether it be science, math, language, philosophy, history, or mechanics. I really do think (and here I will wax philosophic so you can stop reading now if you so desire) that the gristmill of life is such a crushing thing that without some ability to handle it, to think through the weirdness of our human condition and mature into rational adults, we will be destroyed; even if we go on living physically, our minds and spirits get ruined - darkened - fall into a sort of malaise of despair or monotonous repetition which is hellish. The true job of the teacher is to try and provide the ability to see order, structure, pattern and beauty in the world by means of rational thought and contemplation; the constant questioning of "why is this so?" or "what is the pattern?" or "how does this fit?" In short, teaching is a revelation that there is an order to things, a Logos, and that the Logos is beautiful.

Very Platonic of me, I know, but there it is.

************************

He asks: P.S.- In class yesterday we discussed the poem "Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening" by Robert Frost. I could't help but notice some similarities with the story of Dante's Inferno. Is this just me or do you see what I am referring to?

Respondeo ad eum: It's just you. No, seriously, I just finished teaching this and found some excellent material on this poem and on "Road Not Taken" which I will gladly share with you when YouTube is working again. I wrote several essays on the blog (ScribbleBibble) regarding different Frost poems. The connection btwn "Woods" and "Inferno" is very strong - woods, cold, darkness, despair, the longing for sleep - but did Frost intend that? Is there evidence that he was referring to that work or is it just similarly used natural symbolism (which, after all, is a bit limited as it only means what it is and not what we say it is).

Tuesday, July 21, 2009

The convergence of the three

The dream -

In the Song of Solomon Chapter 3 one reads that

By night on my bed I sought him whom my soul loveth:

I sought him, but I found him not.

I said, I will rise now, and go about the city;

In the streets and in the broad ways I will seek him whom my soul loveth:

I sought him, but I found him not.

The watchmen that go about the city found me;

To whom I said, Saw ye him whom my soul loveth?

It was but a little that I passed from them,

When I found him whom my soul loveth:

I held him, and would not let him go,

Until I had brought him into my mother's house,

And into the chamber of her that conceived me.

I adjure you, O daughters of Jerusalem,

By the roes, or by the hinds of the field,

That ye stir not up, nor awake my love,

Until he please.

Who is this that cometh up from the wilderness

Like pillars of smoke,

Perfumed with myrrh and frankincense,

With all powders of the merchant?

Behold, it is the litter of Solomon;

Wollstonecraft in Vindication writes:

A. image -----(degree of truth)------> B. reality

The point of the faith life is to unite image and reality as closely and honestly as possible such that we are able to love that which is lovable. The metaphor for this is a marriage union between man and woman. Image unites with reality so that the mask and the masker are the same and the dancer and the dance are one.

But our problem is manifold. First, we can't handle a great deal of reality, so we have to cloak the reality in layers of imagery. As people mature in their spiritual life they are able to comprehend more beyond the initial image; not losing the initial image (though that is a risk and often seems to result in loss of faith completely), but rather a looking beyond, like Bilbo looking out over Mirkwood.

Second, we have a tendency to cling to our images - to concretize them and insist that the image, not the thing imaged, is the real. Problematic, esp. when we then try to impose these (artificial) concretizations upon others, insisting they live and think the same way as we.

Third, b/c we are so good at self-delusion we frequently construct an image which we know to be wrong - willfully avoiding the images that work in favor of the images that will allow us to get our way; we manipulate images to enforce the dominance of our will over others. This is necromancy.

All this on the natural lacuna, the abyss that occurs as a consequence of the distance between images and reality. Images always fall short of reality and thus need to be abandoned at some point. EVERY image must be abandoned if we are to truly understand either image or reality. This "dark night of the soul" or negative vision, is, it seems, a necessary part of the whole spiritual exercise but probably also the hardest as it is the most terrifying and difficult to accomplish. Those who are afraid of it shy away and retreat to their concrete images, become literalists and doctrinalists, and never enter again the realm of questioning and darkness. Those who are untrained to go through this experience come to think that every image is bogus and all faith is a lie; they cease to question what faith even means (or what terms like "soul", "God" "heaven" or "hell" could mean). Thus they fall into atheism, ridicule or critique of all faith. Rather than trying to comprehend what faith actually seeks to accomplish, namely coming to love that which is lovable, which

cometh up from the wilderness

Like pillars of smoke,

Perfumed with myrrh and frankincense

Note to self: Read more Ratzinger

There be dragons!