In Book X of the Republic Socrates suggests that for the city to be perfect the poets (and all other arts by extension) must all be exiled citing “an old quarrel between philosophy and poetry”. Indeed, artwork is "that 'yelping bitch shrieking at her master,' and 'great in the empty eloquence of fools.' But the real reason of the exile is due to the comfort which art gives. Artwork becomes overly comforting and charms us into a false sense of security, yet offers no real solution to the problem:

In Book X of the Republic Socrates suggests that for the city to be perfect the poets (and all other arts by extension) must all be exiled citing “an old quarrel between philosophy and poetry”. Indeed, artwork is "that 'yelping bitch shrieking at her master,' and 'great in the empty eloquence of fools.' But the real reason of the exile is due to the comfort which art gives. Artwork becomes overly comforting and charms us into a false sense of security, yet offers no real solution to the problem: …if poetry directed to pleasure and imitation have any argument to give showing that they should be in a city with good laws, we should be delighted to receive them back from exile, since we are aware that we ourselves are charmed by them. But it isn’t holy to betray what seems to be the truth.

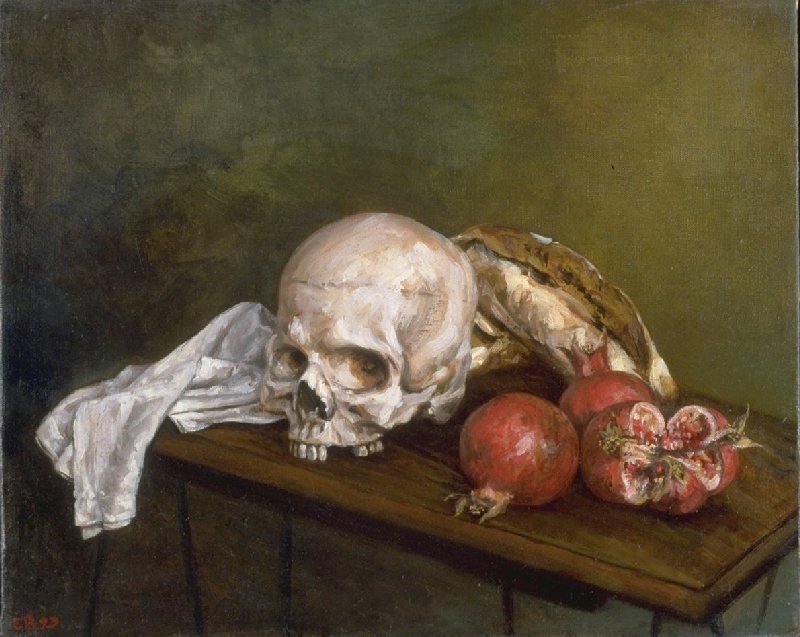

Artwork charms the soul yet its “imitation is surely far from the truth.” Artwork is, in a way, a form of wizardry, an illusion which, even in its best form, only imitates the real but is not the real; “the maker of the phantom, the imitator, we say, understands nothing of what is but rather of what looks like it is.” The image which music, art, sculpture, or story creates c aptures some essential part of reality and as well as it captures reality we say it is “true”. Truth is the proximity of image (eikon) to the real. But between eikones and the good/real there is always a gulf, a lacuna or abyss, which cannot easily be breached; art is still only shadows on the cave wall. We have no assurance that any of the stories we tell, or music we enjoy, or artwork we pleasure in viewing has any connection to anything real; it may just be pleasant fairy tales told to children in order to prevent night fears. Art may be no more than “lies breathed through silver.”

aptures some essential part of reality and as well as it captures reality we say it is “true”. Truth is the proximity of image (eikon) to the real. But between eikones and the good/real there is always a gulf, a lacuna or abyss, which cannot easily be breached; art is still only shadows on the cave wall. We have no assurance that any of the stories we tell, or music we enjoy, or artwork we pleasure in viewing has any connection to anything real; it may just be pleasant fairy tales told to children in order to prevent night fears. Art may be no more than “lies breathed through silver.”

If this is the case man is left with a terrible, unhealing wound. If our art does not connect to reality than how are we to know that we haven’t had generation after generation lying to each other and building on the lies until we no longer know the truth? Do we act the part of iconoclast and tear all the images down? It seems Plato is suggesting exactly that, when he suggests abandoning the old loves of our youth;

…just like the men who have once fallen in love with someone, and don’t believe the love is beneficial, keep away from it even if they have to do violence to themselves; so we too – due to the inborn love of such poetry we owe to our rearing in these fine regimes – we’ll be glad if it turns out that it is best and truest. But as long as it’s not able to make its apology, when we listen to it, we’ll chant this argument we are making to ourselves as a countercharm, taking care against falling back again into this love, which is childish and belongs to the many.

We are, at all events, aware that such poetry mustn’t be taken seriously as a serious thing laying hold of truth, but that the man who hears it must be careful, fearing for the regime in himself, and must hold what we have said about poetry.

The Er myth begins with battle, death and fire – Er is on the pyre when he wakes up from his visionary journey to the afterlife. Those hearing his vision have no absolute assurance that what he says is true, accept that a theophanic miracle has occurred; he has risen from the dead and so ought to know. But the battle, death and fire are themselves metaphorical for that apocalypse of the heart in which all things are transfigured and made new. Without such a transformation one’s loves, belief and understanding of art, life itself remain in an childish world of unquestioning fantasy, insensate and oblivious to the world around us. Real life is not possible in this state any more than it is possible in the realm of the tyrant who imposes his own will. One cannot be a tyrant or a child but must

… accept the fall of the dice and settle one’s affairs accordingly – in whatever way argument declares would be best. One must not behave like children who have stumbled and who hold on to the hurt place and spend their time in crying out; rather one must always habituate the soul to turn as quickly as possible to curing and setting aright what has fallen and is sick, doing away with lament by medicine.

What we are up against, our own misery, loneliness, and unavoidable annihilation are so daunting a hurt that they may leave us howling. But in this, Plato seems to suggest, we have to be men. Life is terrifying; our own oblivion almost unbearable. Yet we must look into it; we have to grapple with the angel of destruction and in that barren landscape have all our most cherished images and stories stripped away in an apocalypse of iconoclasm. Only then is the new heaven and earth able to occur; only then can the myth of Er be granted as something truly beautiful evocative of love.

What we are up against, our own misery, loneliness, and unavoidable annihilation are so daunting a hurt that they may leave us howling. But in this, Plato seems to suggest, we have to be men. Life is terrifying; our own oblivion almost unbearable. Yet we must look into it; we have to grapple with the angel of destruction and in that barren landscape have all our most cherished images and stories stripped away in an apocalypse of iconoclasm. Only then is the new heaven and earth able to occur; only then can the myth of Er be granted as something truly beautiful evocative of love.

Before he died my father kept asking what the story was; "what is the story?" and warning against losing the story; protecting against losing the story. What then is Plato suggesting? Yes, there is one central story that guides us home. But at the heart of things is there no story? no metaphor? no more eikones, image? Only reality? only God all in all? The new Jerusalem on a pillar of fire.

ReplyDelete