Just read an excellent article by Michael Davis in his collection of essays "Wonderlust" published by St. Augustine's Press. The essay entitled "Plato and Nietszche on Death", like most of the essays in the collection, has several penetrating insights. Davis recalls Nietzsche's critique of Platonic thought saying "For Nietzsche the West is in some sense the Christian West, and 'Christianity is  Platonism for the people.'" Indeed, the Christian Church burgeons with Platonic imagery so much so that most people (who do not know Plato) hardly notice the influence, taking for granted their own heritage and thinking that Christianity somehow sprang, fully formed from the brow of Judaism.

Platonism for the people.'" Indeed, the Christian Church burgeons with Platonic imagery so much so that most people (who do not know Plato) hardly notice the influence, taking for granted their own heritage and thinking that Christianity somehow sprang, fully formed from the brow of Judaism.

Platonism for the people.'" Indeed, the Christian Church burgeons with Platonic imagery so much so that most people (who do not know Plato) hardly notice the influence, taking for granted their own heritage and thinking that Christianity somehow sprang, fully formed from the brow of Judaism.

Platonism for the people.'" Indeed, the Christian Church burgeons with Platonic imagery so much so that most people (who do not know Plato) hardly notice the influence, taking for granted their own heritage and thinking that Christianity somehow sprang, fully formed from the brow of Judaism. About the sage Nietzsche's Zarathustra has this to say:

His wisdom is: to wake in order to sleep well. And verily if life had no sense, and I had to choose nonsense, then I too would choose this the most sensible form of nonsense.

The contest between Plato and Nietzsche is, according to Nietzsche, a contest between the view that really makes sense of life and "the most sensible form of nonsense," that is, between truth and the most seductive form of error.

...saved fourteen Athenian youths and maidens from the dreaded Minotaur. ...Phaedo gives an enumeration of those present at Socrates' death, and we discover that fourteen youths are present. Like Theseus, Socrates will save these youths from a dreaded monster.The monster from which Socrates saves his Athenian youths is the dreaded fear of death; not just the cessation of life, but something more. The minotaur is that half man/half bull which breathes ice and devours flesh in the dark; something terrible and cold and inhuman in that maze of the afterlife which devours the mind with despair. As Davis points out, "human beings live better lives when they are not continually haunted by the knowledge of the necessity of their own deaths." Thus the story functions on the level of myth that gives hope to both interlocutors and future generations of readers.

Before we have some mass Cathar suicide ritual going on here, though, we have to recall that Plato himself is not present at the death; he is alive and trying to stay that way (to paraphrase Jack Gilford). So Plato is not suggesting that physical death ought to be pursued. Rather, the fear of death addresses "what Cebes calls 'the child in us who has such fears'". Davis notes that,

The mortal fear of death naturally gives rise to a longing for immortality as its cure. This longing is not a desire to be different from what we are; it is rather a desire to remain eternally what we already are. It is an attachment to ourselves.Everyone, from the slacker to the schoolgirl, from the professor to the pundit, abhors change and wants to be in control of the situation they know. No one wants to endure the suffering which death, in a most radical way, imposes. Thus we delude ourselves, surround ourselves with goodies, abuse each other, lord power over one another, and generally act like spoiled children. Such attachment to ourselves the Greeks called hubris, to which could be attributed every rotten excess of human crime and folly. In the Christian sense, pride (hubris) is the root of all sin (separation from God). Hubris is, essentially, an ingratitude for the goodness which we do not deserve. Thus, we have to grow up. Davis suggests that

Only knowledge of our own immortality can destroy the fears of that child in us and, in a rather radical way, force it to grow up.Those who refuse to grow up avoid facing their own immortality and seek to maximize pleasure. Yet such eternal pleasure is not really possible; "...the complete absence of pain would be possible only given the complete absence of pleasure," as Davis notes, "the natural desire to maximize pleasure, if pushed to its extreme, is a sort of death wish." Yet the same holds true for anyone who longs for an afterlife of eternal pleasure. Since pleasure and pain are yoked together in the individual self, to eradicate one or the other would also eradicate a self to register them. Davis suggests that

...common sense takes as its standard the soul, or life, as it is, and then attempts to imagine what would be the most satisfactory form of such a life. The result is an ideal life, which because it takes its bearings by the extreme... cannot be lived. The ideal verson of life is incompatible with life; it turns out to be a kind of death. This is the tragedy of common sense.Human life is, at root, tragic because we all long for something which would spell the end of us; we long for our own annihilation; oblivion;

a draught of vintage! that hath been

Cool'd a long age in the deep-delvèd earth

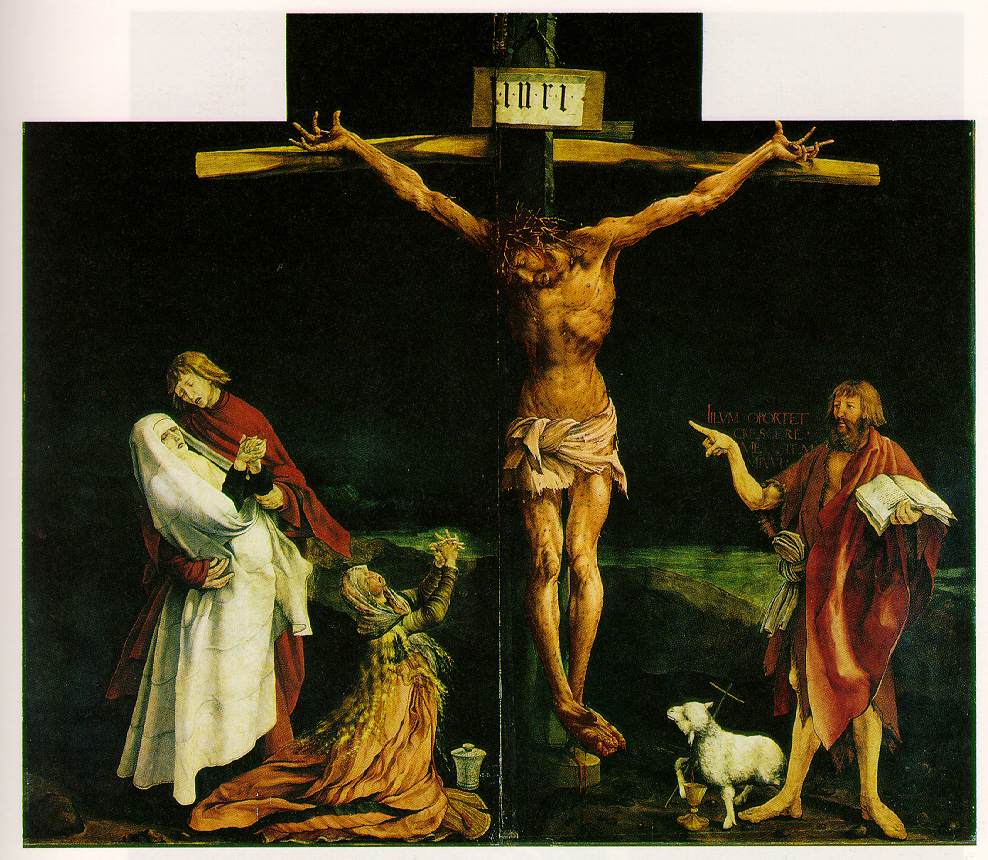

But as Keats noted, to long for such a thing spells our own forlorn doom. "While it is the case," Davis notes, "that the tragedy does not exist for a mollusk, it is also the case that a mollusk does not know that it is a mollusk. The human self seems to be constituted by the conflict between its desire to be what it is and its desire to be other than what it is." So at the very heart of philosophy, represented in Plato by Socrates, is an "awareness of the tragedy of common sense." If we indeed struggle under this crucifying tension of tragedy, why? from whence does it come? what is consciousness that it causes us to weep? and what is man that Thou dost care for him? mortal man that Thou dost love him?

For this reason it is of some importance that the whole question of immortality does not enter Socrates' argument as a means to overcome death. It enters as a means to overcome ignorance.Man must know who he is; gnothi seauton, as the Greeks urged, if he is ever to grow up. Otherwise we stumble about striking, mocking, spitting at, and crucifying one another. But knowing who we are is hindered by the hubristic self-interest that every person bears with them. Self-concern "gets in the way of our pursuit of wisdom... to see the world as it is and not through the lens of our self-interest requires neutralizing self-interest." And to see with such clarity makes one a better person.

So religion (and the "noble lie" of religion) is not such a lie after all but a perspective shift. Davis concludes,

By asserting the existence of a better life after death (even without absolute mathematical assurance of such existence - my own interpolation here) this life is made better. That is, by providing a vantage point from which to judge the goodness of life, the character of this life can be known more fully.

No comments:

Post a Comment